BOFIT Weekly Review 03/2025

Russia’s natural gas and oil exports facing new challenges

Russia’s last operational natural gas pipeline to Europe shuts down

As expected, at the beginning of January Gazprom ended transmission of natural gas via pipelines running through Ukraine. All direct natural gas pipelines from Russia to EU countries (via the Baltic Sea, Poland, Latvia, Estonia and Finland) were terminated already in 2022.

Russia’s 5-year agreement with Ukraine on transhipment of Russian gas via Ukraine’s territory expired on December 31 last year. Ukraine, Russia and the EU reached an understanding in 2019 that permitted the continued transmission of gas via Ukraine to the EU market. The agreement incorporated a separate agreement between the Russian Gazprom and Ukrainian Naftogaz on transhipment during 2020–2024. Despite the war, both parties sought to secure uninterrupted transmission flows. Due to Russia’s full-scale invasion, however, extending the agreement became impossible.

During the first two years of the agreement, 2020 and 2021, the volume of Russian gas transmitted via Ukraine conformed to the agreement’s terms calling for just over 40 billion m3 a year. With Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in spring 2022, the volumes of pipeline gas passing through Ukraine declined sharply. Only 14 billion m3 of gas were transmitted via Ukraine in 2023, and just 16 billion m3 last year. The amount of gas transmitted via Ukraine last year only represented about 5 % of the EU’s total gas imports.

In practice, the only countries recently receiving gas via Ukraine’s pipeline grid were Slovakia and Moldova, with the gas to Slovakia pumped on mainly to Austria and Hungary. Russian pipeline gas still reaches EU countries via Turkey. Two twin pipelines (Bluestream and Turkstream) run along the bottom of the Black Sea from Russia to Turkey. Turkstream’s second pipeline connects to Europe through another pipeline running north through Bulgaria and feeding into the Central European pipeline grid. The volume of gas headed to EU countries via Turkstream has increased significantly since 2022. Last year, the EU imported nearly 17 billion m3 of gas via Turkstream, which is close to the pipeline’s peak capacity.

Transit of natural gas provided Ukrainian and Slovak gas companies with an important source of income for decades, but declining transit volumes have reduced the importance of these incomes. For Ukraine, in particular, most of the agreed transit fees (close to 1 billion euros annually) went to pipeline maintenance. Replacing the lost transit fees may be difficult, but cessation of Ukrainian transit flows has not caused natural gas shortages in EU countries. The gas storage facilities in the EU are full and gas grids between countries have been upgraded. The EU also now has plenty of capacity to import liquefied natural gas (LNG). The cutoff of Russian gas, however, has hit Moldova hard, causing major problems for electricity and district heating production.

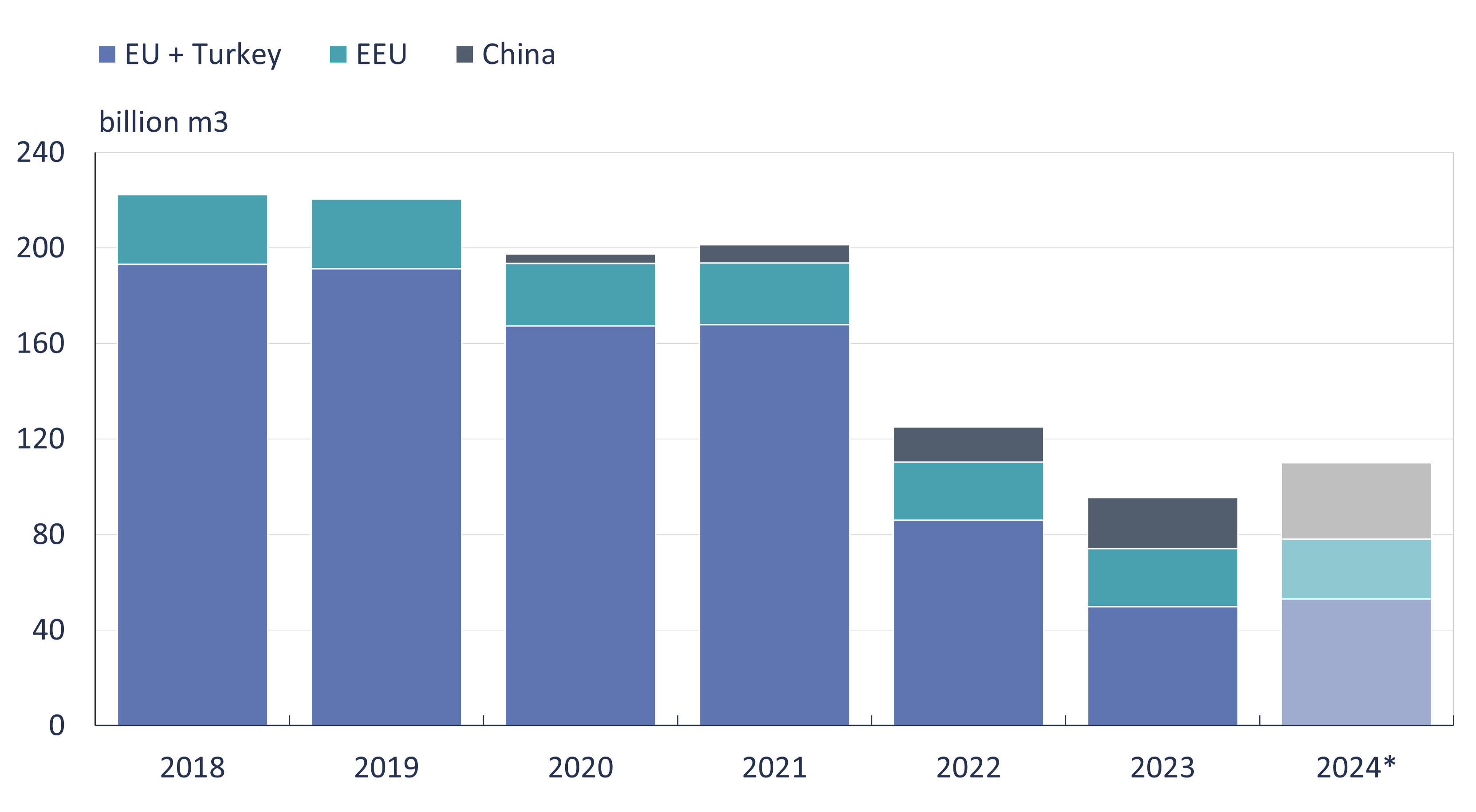

From the Russian perspective, pipeline gas exports have almost halved from their 2018 and 2019 peak level. Gas exports to EU have collapsed due to reduced consumption of gas in Europe, Russian demands for payment in rubles and the EU’s desire to end its dependency on Russian gas. Exports to EU countries last year slightly exceeded 30 billion m3, of which about half went through Ukraine. It will be difficult for Russia to quickly develop alternative export markets. The Power of Siberia gas pipeline running to China already operates at full capacity. Construction of a new pipeline takes several years even with an accelerated schedule. From a global perspective, Norway is now a larger pipeline gas exporter than Russia, a situation not expected to change in coming years. Western sanctions also significantly restrict Russia’s possibilities to expand LNG exports.

Russian pipeline gas exports have fallen to around half of their peak level

Source: Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy 2024 for years 2018–2023. The lighter-shaded 2024 estimates have been compiled from several sources. Exports to the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) mainly represent exports to Belarus.

The US and UK impose a new round of sanctions on Russia’s oil sector

Last Friday (Jan. 10), the United States and the United Kingdom imposed a new round of significant sanctions on the Russian energy sector. The sanction listings include 143 oil tankers suspected for violating sanctions. The US sanctions make it extremely difficult to offload the cargoes of these tankers or provide them with e.g. port services or adequate insurance. Kpler reports that vessels now targeted by sanctions transported about 40 % of Russian seaborne oil exports last year. Most of these vessels transported oil for Russia’s main customers – China and India.

In addition, two large Russian oil companies, GazpromNeft and Surgutneftegaz, were placed on the sanctions list, complicating the ability of these companies to export oil anywhere in the world. The two companies together account for about a fourth of Russian oil exports. Two large insurers are now also under sanctions, making it more difficult to insure vessels carrying Russian oil and raising shipping costs. Newcomers to the sanctions lists included a number of oil-industry services companies, the Vostok Oil project, specific oil-company personnel, as well as shipping companies based in third countries. The US also imposed sanctions on the Vysotsk and Portovaya LNG terminals.

The goal of the current sanctions regime is not to directly reduce Russian exports of crude oil or petroleum products, but rather to reduce the earnings of Russian oil companies. Sanctions increase the costs of production and export for Russian energy companies, whereas the price cap regime imposed by the G7 and EU countries cuts their export revenues. The price cap regime bans insurers, ports, shipping companies and financiers from offering services to any vessel carrying Russian oil or petroleum products if the commercial price of the cargo exceeds the price cap. The price cap for Russian crude is currently $60 a barrel, while caps on petroleum products range from $45 to $100 a barrel. If the commercial price of the cargo does not exceed the price cap, Russian companies not placed on sanctions list can still use vessels from Western shipping companies and purchase insurance from Western insurers.

Prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, about 80 % of Russian maritime crude oil exports was transported by Western tankers. As a consequence of the war, sanctions and price caps, Russian firms have been active in acquiring their own fleet of tankers and making agreements with shippers not based in G7 or EU countries. These vessels are known commonly as Russia’s “shadow fleet.” They typically do not carry Western insurance, and the condition and true owner of these ships is often unknown. At the end of last year, about 80 % of Russian crude oil exports were carried on shadow-fleet tankers.