BOFIT Weekly Review 01/2025

Russia’s 2024 grain harvest falls below expectations

While Russia enjoyed an exceptional bumper grain harvest in 2023 due to favourable weather conditions, the 2024 harvest disappointed with production of major field crops declining to around 125 million metric tons, a 14 % decrease from the previous year. The total wheat harvest last year amounted to 82 million tons, 16 % less than in 2023. Other crops also saw large drops, including maize, barley and sugar beets (all down 20 %) and potatoes (down 10 %). The 2024 harvest reflects poor weather conditions and difficulties in access to high-quality seed, certain farm machinery & equipment. Occasional labour shortages have also been reported.

Despite the bad harvests, Russia remains fully self-sufficient in many staple items. To stabilise domestic food prices, Russia has restricted exports of most grain crops. For example, the quota on wheat exports for spring 2025 is slightly less than 11 million tons (down from 29 million tons in 2024). Exports of rice have been banned completely until June 2025.

Exports within quotas are generally subject to an export tariff based on the difference between the export price and the administratively set reference price. However, Russia has created a regulatory exemption from tariffs on within-quota grain exported from occupied areas in Ukraine to third countries. Separating grain stolen from Ukrainian producers from Russia’s grain exports.

Export restrictions impact the profitability of domestic producers. Regulation of domestic market prices through restricting exports puts pressure on the government to grant additional farm subsidies. New investment for such things as seed, machinery, storage or product development would be difficult to justify based solely on prevailing market prices or export prospects.

Russia’s agricultural production struggles affect its animal husbandry industries. The growth of milk production on dairy farms, for example, ended in spring 2024, with the result that milk production for the first 11 months of 2024 was on par with production in the same period in 2023. Media reports indicate that many dairy farms cut back on production of butter in the second half of the year due to increased production costs. The widely publicised contraction in egg production, which began in 2023, ended last summer. Egg production was up slightly in the second half of 2024. The government quelled the egg crisis, which was precipitated by soaring retail prices in the second half of 2023, through a mix of price controls, lifting of restrictions on egg imports and support programmes for domestic producers.

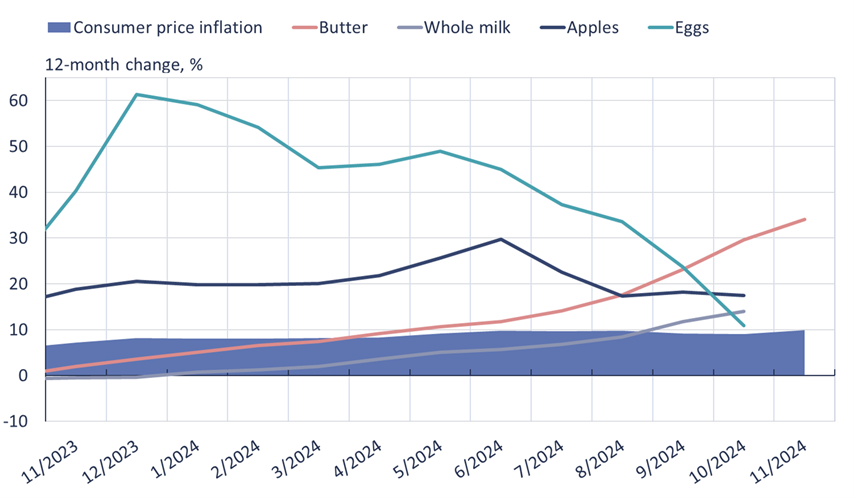

The meagre 2024 harvest and supply-chain issues have impacted the food industry. Foodstuff production slowed from a 6 % on-year rise in the first half of the year to just 1 % in the second half. The slowdown in growth has contributed to the rapid rise in food prices. Food prices in November 2024 were up overall by 10 % y-o-y, but certain products experienced more dramatic price rises.

As an example, butter prices in November were up 34 % y-o-y, while retail prices for milk and other dairy products rose by 14 %. Officials have responded with standard solutions such as easing import restrictions, directing local government officials to monitor local pricing practices and urging competition officials to investigate instances of suspected price manipulation. Further, import tariffs on e.g. butter, apples and potatoes have been suspended until mid-June.

Dairy products last year joined other food prices in exceeding Russian consumer price inflation

Sources: Rosstat, CEIC, BOFIT.

The New Year starts with tax hikes, higher fees and ongoing subsidy programmes

The income tax for all corporations in Russia went up at the start of the year. Other hikes include the recycling fee for farm machinery. The recycling fee, a one-time tax included upon purchase of new equipment, rises by 500 % from last year. It applies to farm machinery where domestic production is seen as sufficient to cover demand. The arrangement is intended to support domestic industry and import substitution programmes, as well as Russia’s efforts at promoting “technological sovereignty”. Because the increase in machinery prices caused by the tax hike is meant to be calmed by tightening price controls, its impact on the profitability of domestic producers is impossible to estimate. With the waning of import competition, however, it clear that the supply of agricultural machinery will decrease, and prices of end products will rise.

Agricultural budget subsidies are part of federal and regional support schemes, as well as loan interest subsidies granted at the federal level. The government has promised to keep subsidies this year at similar levels to those of 2024. In particular, dairy livestock production has been promised more subsidised-interest loans than in previous years. Interest rates for subsidised loans to priority branches of agriculture and the food industry have been limited to 5 % since 2017.

Russia is a top wheat exporter, and the state’s role in arranging many aspects of exports has increased in recent years. At the end of 2024, the interest group representing grain exporters (Sojuz Exporterov) listed 13 countries outside the Eurasian Economic Union that only direct government buyers will be eligible for grain exports. Although not in the form of an official decree, the guidance effectively limits the role of foreign brokers in arranging export trading. Russian grain exports travel mainly through Black Sea and Azov Sea ports. In addition, Russia exploits ports on the occupied Crimea. In recent years, the government has assumed direct or indirect majority control in most of the export terminals in these ports. State-owned banks, and VTB in particular, have increased their ownership stakes in agriculture-related branches.

Large-scale farming companies control most Russian grain production

About two-thirds of Russian farmland is classified as government-held. Private landholders oversee about 130 million hectares of farmland, of which about 24 million hectares are in the hands of large agricultural holding (agroholding) companies. The lion’s share of Russia’s grain harvest is grown in the fields controlled by giant agroholding companies. In 2024, over 70 % of grain and nearly 90 % of sugar beets were harvested on lands held by agroholding companies. Official figures show that private small farms still produce many other crops, including potatoes and most vegetables.

A recent study released by the consulting firm BEFL found that, as of May 2024, Russia had 40 large agroholding companies holding at least 150,000 hectares of farmland. The country’s biggest meat producer Miratorg and Agrokompleks (which is owned by former agriculture minister Alexander Tkachov) each had landholdings of more than a million hectares of farmland. Large agroholding firms have gradually increased their landholdings and production. The landholdings of Russia’s large agricultural firms ten years ago amounted to roughly 16 million hectares of farmland.