BOFIT Weekly Review 25/2016

Rapid lending growth in China continues

China’s own broad credit stock measure, total social financing (TSF), grew 13 % y-o-y in May. Credit growth remained stable throughout the first five months of this year, rising about twice as fast as nominal economic growth. Yuan-denominated bank loans, the largest of TSF’s subsets, were up 14 % y-o-y. Lending of the shadow banking sector (trust and entrusted loans) showed high growth. The stock of forex-denominated loans continued to shrink, as yuan weakness and uncertainty over future exchange rate trends reduced borrower interest in new forex loans, and borrowers increasingly paid down debts in foreign currencies.

China adopted the TSF measure in 2011 to capture the rapid growth in non-traditional financing activity (i.e. the use of credit forms other than bank loans). Lately, however, doubt has been cast on the TSF indicator’s ability to capture credit creation. Analysts at Goldman Sachs estimated at the beginning of this month that the volume of credit creation last year was about 30 % higher than the TSF figure.

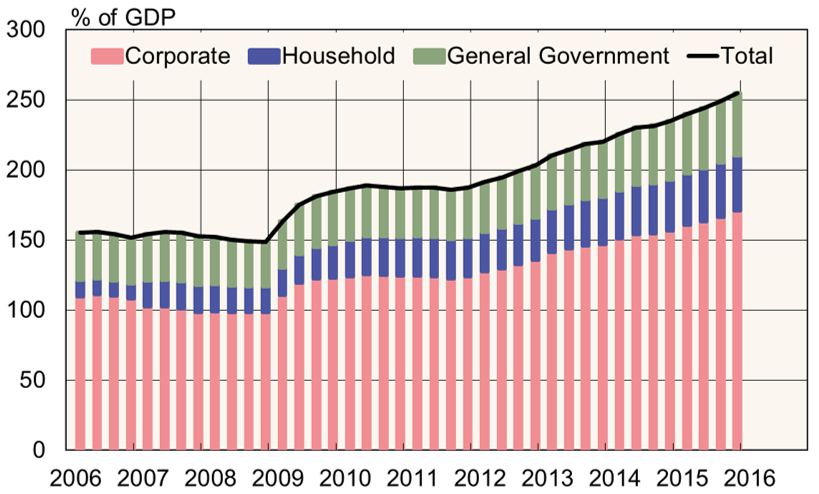

The Bank for International Settlements (BIS) reports that China’s total debt at the end of 2015 was equivalent to about 255 % of GDP, a level far higher than is typical for emerging economies. The ratio of corporate debt to GDP was 171 %, public sector debt 44 % and household debt 40 %. Because the state is also an active participant in the corporate sector, it is difficult to differentiate public-sector and corporate debt. The IMF, for example, puts China’s public sector debt at around 60 % of GDP. Given the strong rise in borrowing in the first five months of this year, the debt ratio already likely exceeds 260 % of GDP.

China’s debt structure

Source: BIS.

Despite years of incessant debt rise, China has made limited progress on tackling the issue. The IMF last week warned that China’s government needs to promptly get a handle on already high – and rising – corporate debt to avoid serious problems. The IMF would like to see China move ahead with measures such as stricter budget constraints for state-owned enterprises, restructuring or closing down problem firms and preparing to deal with the ensuing social costs. The experiences of other countries suggest that sustained rapid rises in credit growth are likely to end in financial market meltdowns and severe economic slowdowns or even economic contractions. The good news in China’s case is that it may still manage to deal with its debt problems as nearly all debt is denominated in yuan and the state controls large financial buffers that it can deploy to avoid a systemic crisis.