BOFIT Weekly Review 43/2018

Little progress in core reform of China’s state enterprises

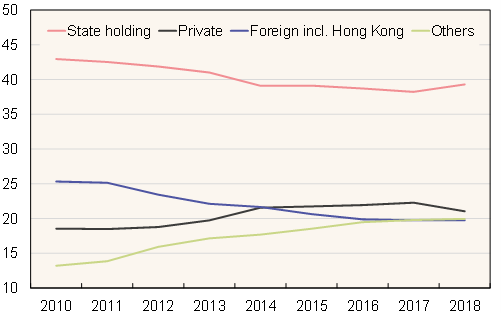

In recent years, China has implemented various programmes and subsidies to make state-owned enterprises (SOEs) bigger and stronger while limiting options for companies in the private sector. The share of industrial assets of SOEs have slightly increased this year after falling earlier.

As economic growth has slowed, concerns over future growth has increased and international criticism of China’s SOEs has grown, China’s leaders have responded by talking more about the importance of the private sector. A letter by president Xi Jinping published last weekend stressed the importance of the private sector. Vice premier Liu He has recently also come out as an ardent advocate for the private sector.

The most critical move in helping the private sector would be to create a level playing field. Most of China’s financial sector is in state hands and bank lending policies tend to favour state companies no matter what their financial condition or whether their projects make any financial sense. Banks assume SOEs enjoy implicit state guarantees that will protect them when risk materialises. This distorts the pricing of risk, which has allowed many SOEs to become over-indebted. Allowing firms to go on reckless borrowing sprees means that banks likely hold large stocks of bad loans. Chinese government has long been urged to end implicit state guarantees to SOEs to end this distortionary effect.

Even if modernisation of SOEs is a central tenet of structural reform, little progress has been made on this front. A campaign was launched some years ago to sell partial stakes in SOEs to private investors (mixed-ownership reform), but the results to date have been modest. In some cases, SOEs have been sold to active management.

A big problem in pushing through reforms is that they may conflict with the interests of the decision-makers themselves. SOEs have tight connections with political decision-makers, with corporate leaders typically tapped by the party elite. This creates a system that cycles the same people through executive ranks of state-owned firms, top positions at decision-making bodies in public administration and high regulatory posts. Decision-makers also use SOEs as instruments for implementing economic policy in order to guarantee that they meet politically defined growth targets. Giving up of such direct tools is difficult. Connections to SOEs are often important in personal career advancement within the party hierarchy and wealth accumulation.

Currently, 96 conglomerates operate under the auspices of the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC), which works directly under the central government. The government has reduced the number of such conglomerates through mergers. The OECD reports that when the number of subsidiary corporations within conglomerates and other firms directly under central government administration are included, there were about 50,000 such firms at the end of 2015 employing 20 million people. When local-level firms and their subsidiaries are included, some 160,000 SOEs operated in China at the end of 2015. 25,000 of these firms were involved in industry, 15,000 in the real estate sector, 13,000 in primary production and 10,000 in the transport sector. The OECD reports that these firms employ a total of 40 million people, with 11 million engaged in primary production, 7 million in industry and 5 million in the transport sector. By some official estimates, Chinese SOEs employ around 60 million people. In any case, SOEs employ a relatively small part of the Chinese workforce (770 million), but enjoy a disproportionate share of many other resources.

Share of industrial assets by ownership, %*

* Situation in August of every year.

Sources: CEIC, NBS and BOFIT.