BOFIT Weekly Review 12/2025

China’s public sector deficit set to rise this year

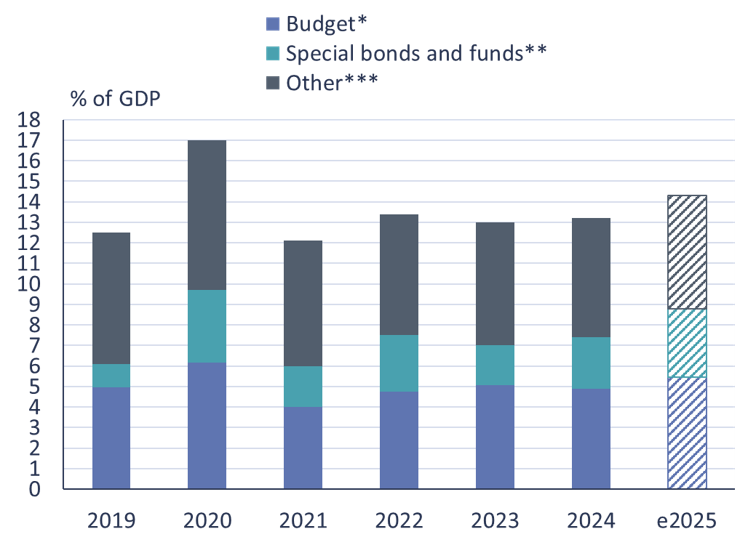

China’s official 2025 budget, which was approved last week by the People’s National Congress, generally adheres to the “major tasks” set forth in the government’s work report (BOFIT Weekly 10/2025). The finance ministry expects total budget revenues of central and local governments to remain around the 2024 level of roughly 22 trillion yuan (15.5 % of GDP), while more than 2 trillion yuan in unspent budget funds from last year will be rolled over for use this year. Budget spending overall will rise this year by 4 % to nearly 30 trillion yuan (20 % of GDP). The finance ministry projects a public sector budget deficit this year of 4.0 % of GDP (5.7 trillion yuan), a one-percentage-point increase from 2024. When China’s these budget figures are adjusted for international comparison, the budget deficit grows slightly to 5.5 % of GDP this year, up from 4.9 % last year.

A considerable amount of public sector activity in China takes place off-budget, so shifts in the budget deficit do not necessarily indicate changes in the direction of fiscal policy. The finance ministry currently reports three off-budget items: government-managed funds, state capital operations and social security funds. Of these three, government-managed funds are most crucial to setting the tenor of fiscal policy, as they include funding of central and local government activities with special purpose bonds. Both central and local government expect to increase their special-purpose bond issues this year. According to the finance ministry, the central government plans to issue 500 billion yuan in special bonds this year for bank recapitalisations and 1.3 trillion yuan in ultra-long maturity bonds, of which 800 billion yuan will be used on “major national strategies and security capacity-building in key areas” and 500 billion yuan on the household appliance rebate programme and supporting upgrades of corporate equipment. Local governments can issue 4.4 trillion yuan in special-purpose bonds for financing their own projects, which is 500 billion yuan more than last year (not counting the debt restructuring launched at the end of last year). Total special borrowing should rise by nearly 1 trillion yuan to over 6 trillion yuan this year (again, excluding debt restructurings), i.e. roughly the same amount as the formal budget deficit.

In addition to the items included in the headline budget and other finance ministry reporting, local governments have circumvented their debt restrictions through the establishment of the local government financial vehicles (LGFVs) in order fund projects and stimulate economic growth. Many local governments have struggled with debt since the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic and the collapse of the real estate sector. China’s government has long refused to acknowledge LGFVs as part of the public sector, but under the broad-based “stimulus programme” launched last year at least some of LGFV “hidden” debt are transferred to local government accounts. During 2024–2026, local governments are permitted to issue annually up to 2 trillion yuan in special-purpose bonds for paying off these “hidden” high-interest LGFV loans (BOFIT Weekly 46/2024). By some estimates, China’s hidden LGFV debt amounts to around 60–70 trillion yuan, so the programme is just a drop in the bucket. The IMF estimated last summer that project funding channelled via LGFVs this year will amount to nearly 4 % of GDP, a slight decline from 2024. LGFV borrowing, however, is very difficult to forecast, and stricter economic policies could cause the deficit to contract faster than the IMF’s basic scenario. Besides LGFV debt, public projects are also financed through government-guided funds, which, the IMF estimates, could amount to nearly 2 % of GDP this year.

Altogether, the estimates of the finance ministry and the IMF as to China’s public sector off-budget borrowing suggest that the public sector deficit (broadly defined) will grow by just over one percentage point from around 13 % of GDP this year to over 14 % next year. If the LGFV borrowing will shrink more than expected, the growth of the broader public sector deficit will be lower than expected. Due to the large persisting deficit, public sector debt is expected to reach roughly 130 % of GDP at the end of 2025.

Most of China’s public sector deficit is off-budget

*) The finance ministry’s reported budget deficit in internationally comparable form. **) The finance ministry’s reported estimated deficits (surpluses) in government funds, as well as central and local government measures funded with special-purpose bonds. ***) The IMF’s estimate of deficits of LGFVs and government-guided funds.

Sources: IMF, China’s finance ministry and BOFIT.