BOFIT Weekly Review 03/2023

Russia’s government spending soars while war and sanctions caused various government sector revenue categories to tumble

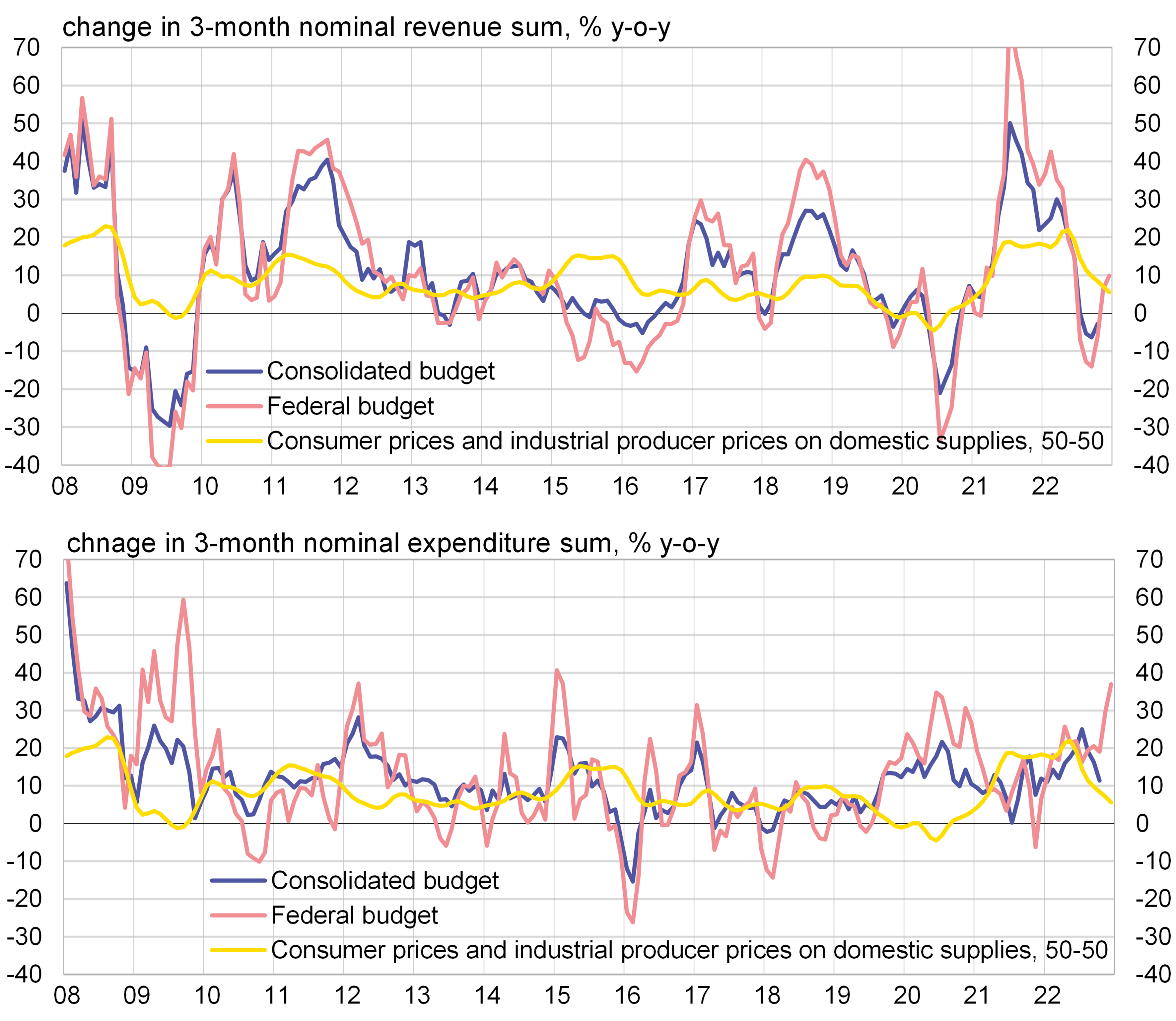

Russia’s downward slides in the economy and imports since its delusional invasion of Ukraine eleven months ago have substantially depressed Russia’s government revenues. The consolidated budget, which comprises federal, regional and local municipal budgets plus state social fund budgets, has seen nominal revenues decline significantly on-year since mid-summer 2022 (consolidated budget information is only available through October 2022). The same applies to federal budget revenues, which account for over half of consolidated budget revenues. In the final months of last year, the federal budget got a boost from a huge production tax imposed on state-owned Gazprom. As a result, nominal federal budget revenues briefly exceeded 2021 levels. Without the Gazprom windfall, revenues would have continued to slide.

In terms of real purchasing power, revenues to both the consolidated and federal budgets headed downward since late last spring, when spiking inflation outpaced the nominal rise in revenues (measured broadly as an even split between the change in consumer prices and industrial producer prices for domestic supplies as spending on government wages and social supports constitute about half of consolidated budget spending). While inflation slowed significantly in the second half of 2022, consolidated budget revenues were still down in real terms by 10−15 % y-o-y in autumn and federal budget revenues were off by 15−20 %. Indeed, without the Gazprom money, the downward (albeit less severe) trend would have continued in the fourth quarter. Earlier Russian recessions have caused similar real declines in government revenues.

Inflation has largely outpaced growth in Russia’s government budget revenues since late last spring, real spending has risen.

Sources: Russian Ministry of Finance and BOFIT.

The basket of consolidated budget revenue streams other than those from special taxes on the oil & gas sector, which account for about 80 % of total revenues, went into decline on-year last summer. In the federal budget the shortfall emerged already late last spring. While war and sanctions depressed output, spiking Russian inflation (also due to war) fuelled a rapid rise in nominal GDP (the highest since 2011 not counting 2021). This raised revenues from value-added and excise taxes on domestic producers (an over 13 % share of consolidated budget revenues in 2021) during the entire year. Tax collection seemed relatively strong as the ratio of VAT revenues to GDP stayed close to its 2021 peak.

Despite recession, the economy’s wage sum rose at a comfortable pace, lifting labour income tax revenues (10 % share of consolidated budget revenue). Revenues from social taxes on wage payments (a 19 % share), however, were down markedly on-year after an extension on paying them. The situation began to stabilise in autumn. Revenues from corporate profit taxes (13 % share) fell sharply went into freefall around mid-summer.

War and sanctions have been particularly hard on revenues from VAT on imported goods and import duties (10 % share), which already by late spring were down by 40−45 % y-o-y. Figures in the autumn still showed an on-year decrease of about 25 %. The last time Russia experienced a similar drop in VAT on imports and import duties was during the harsh recession of 2009.

Revenues from production taxes and export duties on the oil & gas sector, which together account for about a fifth of consolidated budget revenues and about 40 % of federal budget revenues, were down significantly on-year around mid-summer. Decisions by Western firms to reduce their Russian oil imports compelled Russia to large discounts on Urals blend crude oil as early as March, even if the Urals price underscored the level of 12 months earlier only in early autumn. On the other hand, the value of oil & gas taxes, which are denominated in dollars, declined in ruble terms as a very large current account surplus and stringent currency controls drove up the ruble exchange rate sustaining from late spring until virtually end-2022. A slight increase in oil output lifted the share of oil production tax revenues in all oil & gas tax revenues to over 72 %, while Gazprom’s extra production tax payment raised the share of natural gas production tax revenues.

With the acceleration of consolidated budget spending growth in the spring and slowing inflation, spending increased at a considerable pace in real terms after mid-summer, due e.g. to a sharp increase in spending on fixed investment (information on other spending categories has not been released since April figures). Federal budget spending already accelerated in the months around the invasion of Ukraine and was boosted in the final months of 2022 to about 40 % y-o-y. The dramatic increase in spending on fixed investment points to a sharp rise in defence spending (which was already up by nearly 40 % y-o-y in January-April). The real increase in total government spending, however, has yet to exceed the tempos seen in some of the previous recessions.

With fading revenues and increased spending, the small federal budget surplus (0.4 % of GDP) in 2021 transformed in 2022 in a larger-than-expected deficit (2.3 % of GDP – even with Gazprom’s tax boost equivalent to nearly 1 % of GDP). This situation should characterise roughly the overall government sector deficit as regional and municipal budgets and the budgets of state social funds can hardly finance any deficits. In early autumn, the government still contemplated covering the federal budget deficit with significant drawings from the reserve fund (National Wealth Fund). However, in late autumn it resorted to financing the deficit almost entirely through massive domestic bond issues.

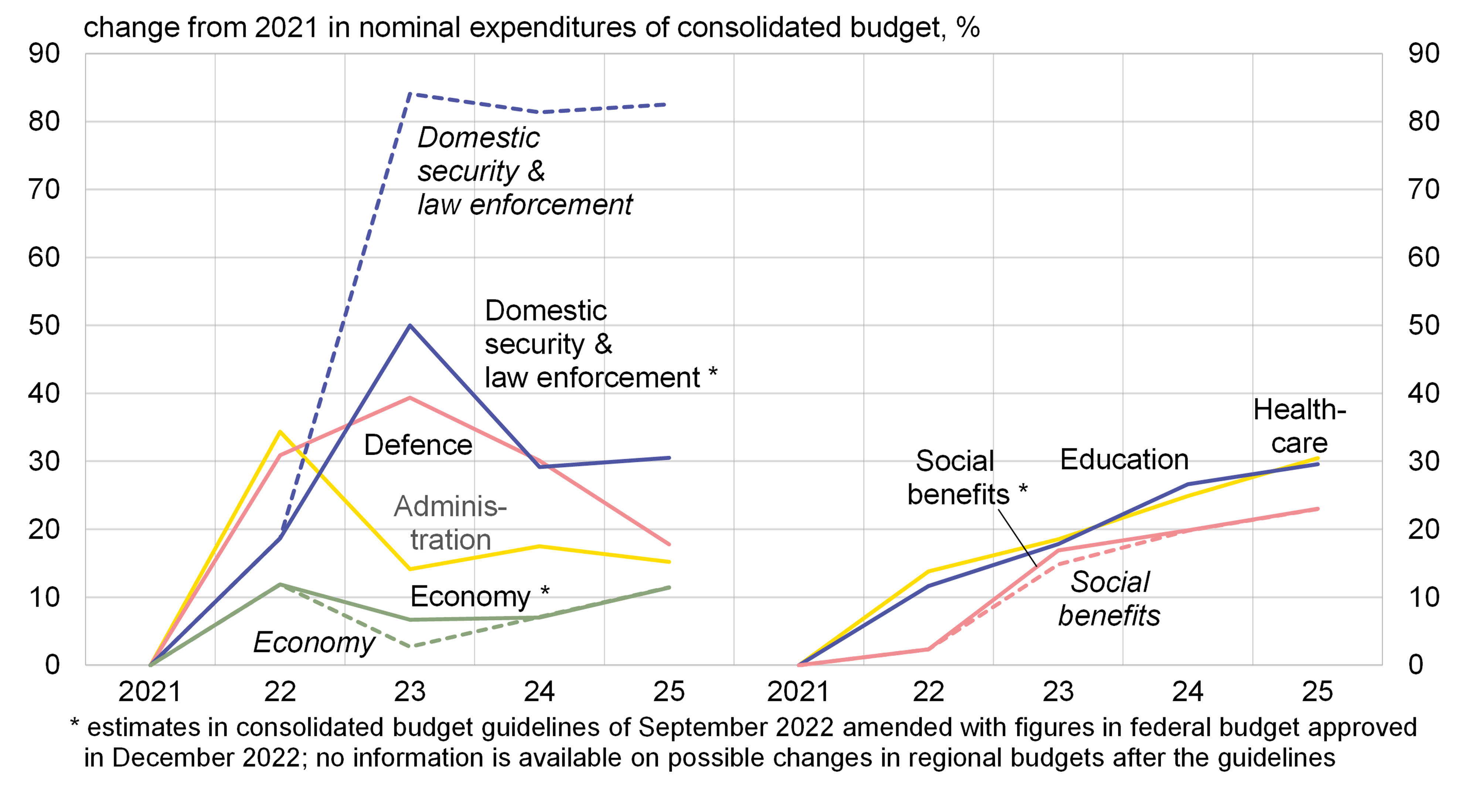

In early autumn, the finance ministry drew up revenue estimates based on a relatively optimistic economic forecast, issued in a government budget policy framework. It also presented a very modest increase in consolidated budget spending that only slightly exceeded forecast inflation. Federal and state social fund spending approved by the Duma in December did not exceed the autumn estimates even if the allocation of federal budget spending (at least at that stage of the game) pulled back on the huge spending increase planned for domestic security and law enforcement and added some spending on sectors of the economy struggling with the current recession. The large and fast excess in federal budget spending last year from what was expected already indicates that existing spending plans and schedules presented in public may see rapid additions this year in circumstances of war and recession.

The current government goal to rein in spending growth is based on limiting the federal budget deficit this year to 2 % GDP. The limit could be exceeded, however, given the overly favourable revenue estimates and extra spending growth. The increase in the budget deficit could be financed from the National Wealth Fund and from large state-owned banks (to which the central bank, in turn, could provide liquidity support as needed) if direct financing from the central bank appeared too unattractive.

Structures of Russia’s government spending have been partly revised since September 2022.

Sources: Russian Ministry of Finance and BOFIT.