BOFIT Forecast for Russia 2025–2027

1/2025, published 24 March 2025

While Russian GDP has risen in recent years, much of the growth has been driven by the surge in government spending on the war in Ukraine. We expect government spending to increase further this year, but production is already stretched to capacity, limiting potential for further output gains. We now forecast a slowdown in Russian annual GDP growth to around 2 % this year and about 1 % in 2026 and 2027. Russia’s economic development is subject to exceptionally high risks as long as Russia continues its war in Ukraine. The incessant rise in government spending and the government’s focus on branches that support the war effort makes structural imbalances in the economy worse. Although a full-blown economic crisis in the immediate future is unlikely, failure to address economic disparities could eventually have serious repercussions.

Preliminary Rosstat reporting shows Russian GDP grew by 4 % last year, a slightly higher pace than predicted in our October 2024 forecast. The strong growth reflects robust increases in government spending, especially on branches involved in the war effort. In the second half of the year growth slowed down substantially. Production capacity is approaching its limits, so increasing output is becoming more challenging. At the same time, structural imbalances in the economy have worsened. The government has run deficits for three years running and consumer price inflation has accelerated to double digits.

Government continues to support production growth this year

Russia’s economic policy framework of previous years remains in place, meaning that provision of necessary economic resources for sustaining the war will remain the top priority. Government spending is set to increase further. The current budget calls for a 10 % increase in spending this year, with nearly all new spending going to the war effort. In addition, major investment projects will be supported through low-interest loans and financing from the National Wealth Fund.

Output growth is expected to slow even with increased government spending. Labour shortages and production capacity constraints mean that growth levels of earlier years are now out of reach, so inflation will accelerate. The central bank must simultaneously maintain a tight monetary stance to rein in inflation. Russia’s key rate was raised to a historic high of 21 %. A high key rate forces up bank lending rates, which then impacts the investment plans of firms not benefiting from government subsidies.

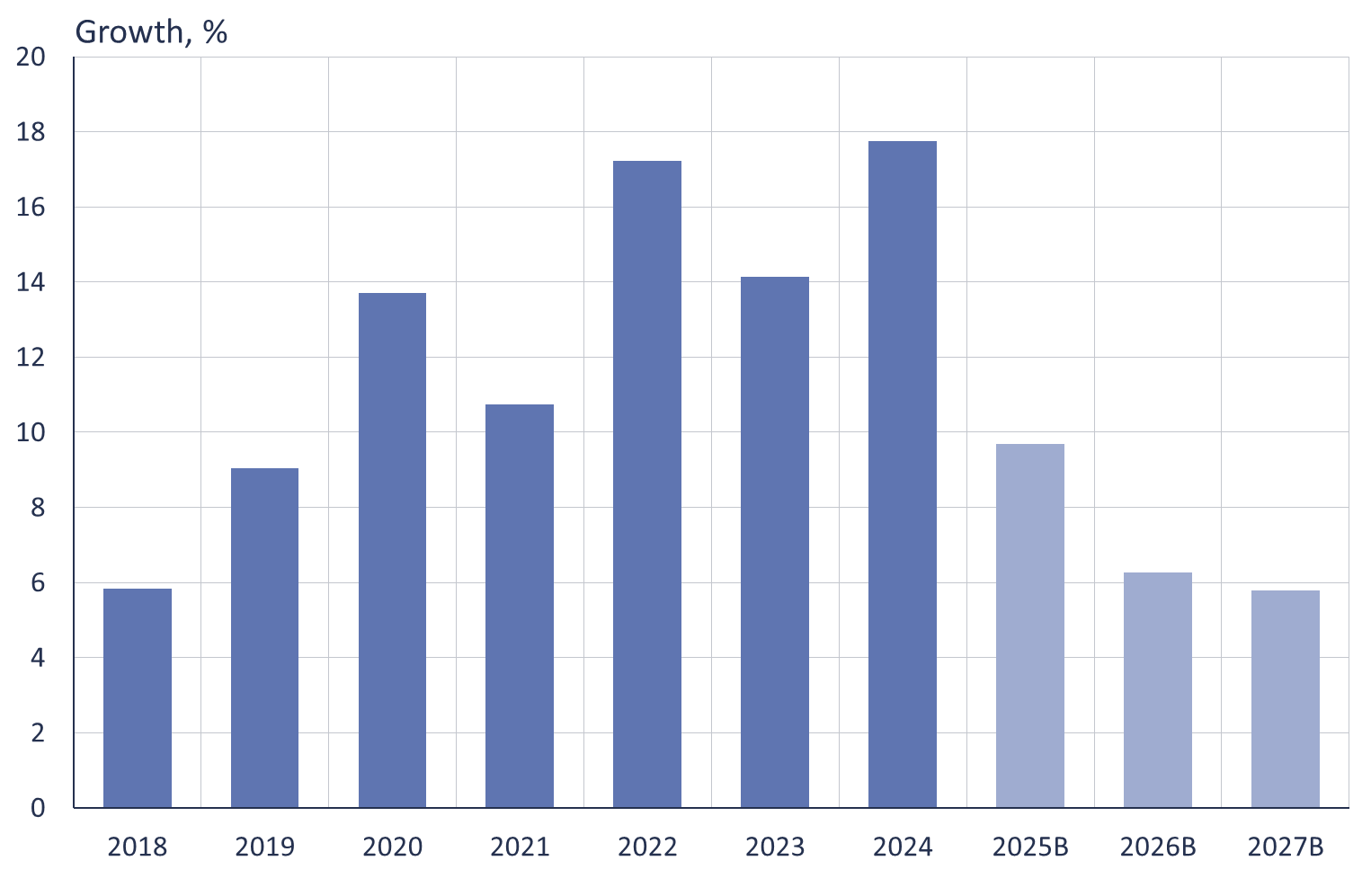

Figure. Russia’s public sector expenditure is growing rapidly

Sources: CEIC, Russian Ministry of Finance, BOFIT.

Private sector demand weakening

The trend in fixed investment of private businesses should weaken this year. Besides high funding costs, investment possibilities are limited by decreasing earnings, rising labour and material costs, as well as an increased tax burden from higher tax rates. Total investment, however, will be sustained by budget financing and other government support measures. While fixed investment overall is not expected to fall this year, growth will be substantially slower than in previous years.

The outlook for private consumption is also bleaker. Purchasing power has been eroded by lower wage growth and rising inflation, and consumer expectations have dimmed. Consumer credit has become more costly and harder to get, and the extensive interest-support programme for housing loans has ended. Despite distinctly lower growth, full employment, modest improvement in purchasing power and spending of household savings should be enough to sustain private consumption this year. The role of the public sector in driving consumption will also become more pronounced.

Weak foreign trade performance to continue

Sanctions have curtailed and impeded Russian foreign trade. Russia has managed to circumvent sanctions to some extent. Led by declines in exports of crude oil and refined petroleum products, the volume of Russian exports apparently slightly declined last year. The dollar-value of imports contracted by 1 % last year, and, due to rising import prices, the volume of imports likely contracted even more. With fading demand growth, ruble devaluation and sanctions stifling imports, the volume of exports and imports should remain at their current levels throughout the forecast period. Absent significant progress in Russia-Ukraine peace talks, we assume no substantial changes in the sanction pressure applied on Russia.

Russia again produced a current account surplus last year ($54 billion). We expect the current account to remain in surplus throughout the forecast period. The current surplus should shrink slightly in coming years along with a drop in the average export price of Russian crude oil. The average export price last year was $69 a barrel. If sanctions pressure is maintained at its current level, the average export price would sink this year to around $61 and below $60 in 2026 and 2027.[1]

Russia still able to fund budget deficits

The vigorous growth in government spending during the war on Ukraine has driven Russia’s government finances into deficit, with deficits running at roughly 2 % of GDP a year since the start of the war. The current budget framework calls for a reduction in the annual deficit to around 1 % of GDP during 2025‒2027. This framework relies on rather optimistic assumptions, however, so the deficit could again turn out higher than planned.

Russia should be well able to fund deficit even larger than what it has budgeted at least for this year. The deficit is set to be financed through increased government borrowing. The Russian government has a fairly low debt-to-GDP ratio (about 20 % of GDP), as well as some liquidity in the National Wealth Fund to draw upon. As of end-February, liquid assets in the National Wealth Fund still amounted to around 3.4 trillion rubles (2 % of GDP), even if two thirds of the Fund’s liquid assets have already been consumed by the war.

Great uncertainty

A great number of risks could affect Russian economic growth as long as Russia continues its war of aggression in Ukraine. The government must continually increase spending to fund additional war activities. While such spending can give a brief boost to production above our forecast, it also worsens structural imbalances in the economy. The central bank must resort to further tightening of monetary policy to curb inflation. While high interest rates hurt the growth possibilities for industries not involved in supporting the war effort, abandoning the tight monetary policy regime could lead to an uncontrollable inflation spiral and economic crisis.

Oil prices, Russia’s relations with China and sanctions are among the most significant external factors affecting the outlook for the Russian economy. A significant tightening of sanctions would weaken Russia’s economic development. A sharp and prolonged drop in oil prices would also significantly curtail Russia’s government finances and ability to make war. Russia’s economy could severely suffer if relations between China and Russia degrade. Russia has become highly dependent on China in recent years.

War has degraded the Russian economy’s long-term growth possibilities, and output gains have relied upon government spending on branches connected to the war effort. Investment in war also diverts assets that could otherwise go to sustained economic growth that promotes national well-being. Russia’s most important goal, however, is to continue the war in Ukraine regardless of the suffering it causes or the costs. For the moment, Russia has sufficient economic resources for that even if the costs become continuously higher.

Table. On-year change in volume of Russian GDP, %

|

|

2022 |

2023 |

2024e |

2025f |

2026f |

2027f |

|

GDP |

-1.4 |

4.1 |

4.1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

Note: 2024 change based on preliminary Rosstat figures. Figures for 2025, 2026 and 2027 based on BOFIT projections. e = estimate; f = forecast.

Sources: CEIC/Rosstat, BOFIT.

What would a ceasefire mean?There is tremendous uncertainty about the course of the war at the time of this forecast. The chances for a lasting peace agreement seem remote, but a ceasefire or truce could bring a cessation in fighting. The impacts on the Russian economy in the immediate aftermath of a ceasefire would remain limited as long as uncertainty about final resolution of the conflict exists. If the fighting ends, Russia could halt the increase in government spending because the costs of war would no longer increase. The spending needed to sustain the war effort is unlikely to diminish, however, as it would go to stockpiling and regenerating resources for future conflicts. Other spending could be cut to balance government finances and assure economic stability. The overheated labour market would cool as new manpower was no longer needed at the front. Economic imbalances would ease as the government’s deficit shrinks and inflationary pressures subside. Lower inflation would support purchasing power and allow for a more accommodative monetary stance. Output growth would still be modest, but it would be on a more sustainable basis than growth driven by government spending in wartime.[2]. If no lasting peace agreement is achieved, the temporary truce or ceasefire agreement would give Russia an opportunity to rebuild its economy for making war later. Russia’s re-arming possibilities are most solid in scenarios involving a truce that leads to a partial lifting of sanctions (even briefly). Larger export earnings would enable Russia to build up new economic buffers. Loosening restrictions on imports would allow Russia to build up its stores of critical import goods and components for the future needs of its military-industrial complex. |

[1] In line with the IEA’s estimate of average Russian oil prices in recent months, we assume the average discount on Russian crude oil will remain around $10 a barrel over the forecast period. This discount has been subtracted from the average Brent crude futures contract price in early March used to forecast price trends for 2025–2027.

[2] The impacts of an end to hostilities and lifting of sanctions are discussed in detail in BOFIT Policy Brief 4/2025.