BOFIT Weekly Review 48/2024

US-China bilateral trade relations remain inflamed

The bilateral relations of the United States and China seem destined to remain difficult. Even if incoming US President Donald Trump has yet to put the finishing touches on his cabinet and other key appointments, it is already clear that the US intends to adopt and implement robust protectionist policies as the US-China trade war enters its seventh year. All the additional tariffs imposed by the first Trump administration remain in force – and more are promised. This week Trump repeated his intention of imposing a 10 % additional tariff on imports from China. China is not the only country in Trump’s sights; he has also threatened to set a 20 % tariff on imports from Canada and Mexico. Trump has even suggested tariffs on all imports to the US with the aim of strengthening the US trade balance and encouraging domestic production. Unfortunately, it is likely that US firms and households end up paying for most of the proposed tariffs, just as they have in the case of the 2018–2019 Trump tariffs (see this recent Bank of Finland blog post).

The US-China conflict reflects China’s efforts to increase its geopolitical role in the global economy. China also seeks technological self-sufficiency and global technological dominance. The US, on the other hand, sees China’s efforts as a threat to its own national security. Poor relations between the world’s two largest economies hurt the global economy due to increased economic policy uncertainty that impairs global trade, hurts business and consumer confidence, and increases market volatility, pricing of risk and the cost of financing. Tariffs and export restrictions also complicate the business environment for international firms. Firms now must diversify their investments and reorder their production chains to mitigate trade policy related risks.

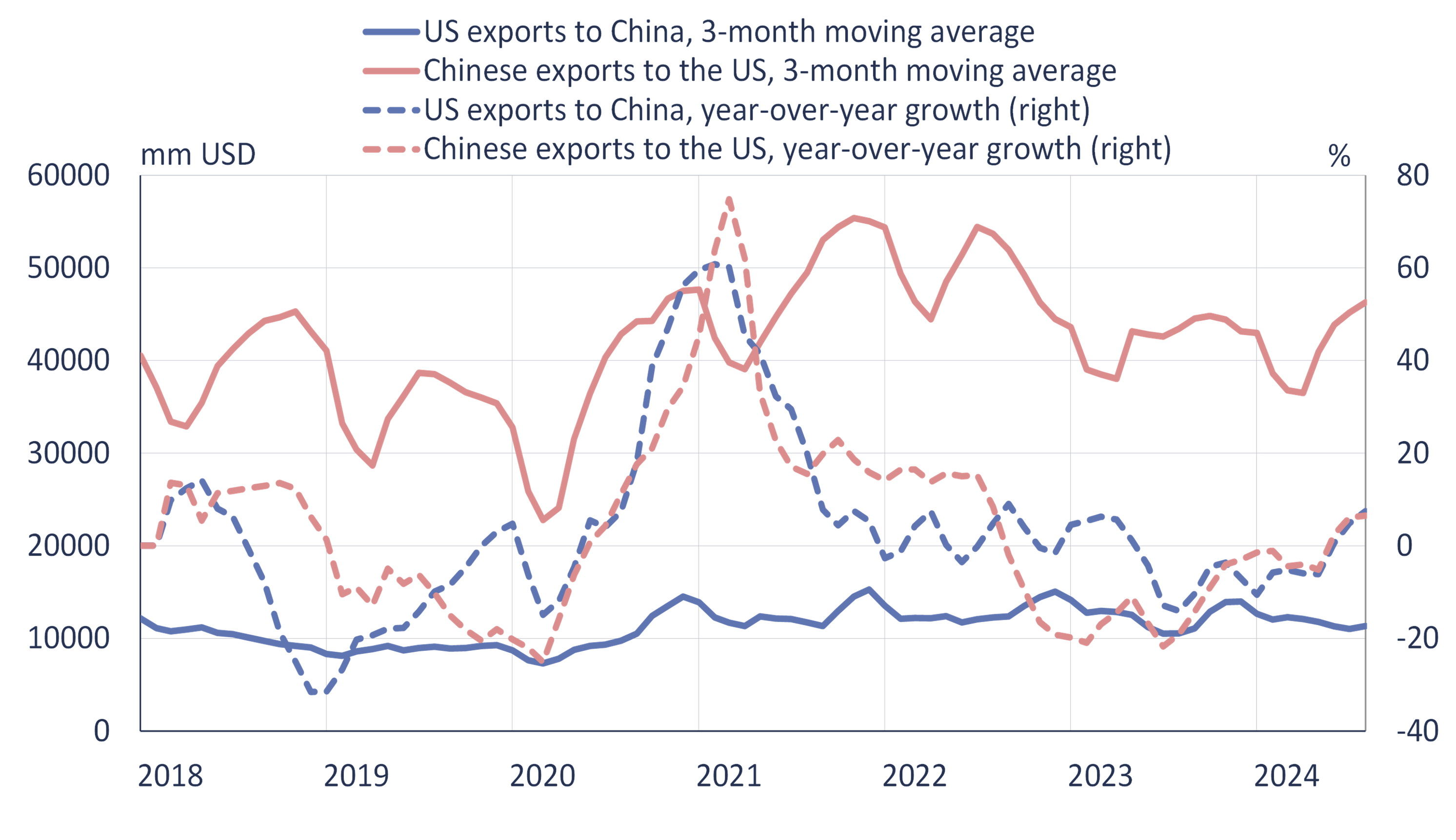

The US-China trade war has caused a shift in the structure of the two countries’ foreign trade. In terms of direct trade, both have stepped away from each other. China now accounts for just over 11 % of US goods trade (imports and exports), down from over 16 % in 2017 before the trade war. The US share of China’s goods trade has fallen from over 14 % to 11 %. Growth of US-China bilateral trade has also been quite sluggish this year, an indication that the countries’ market shares continue to shrink. IMF trade figures show that US exports to China contracted in the first eight months of this year by 0.6 % y-o-y, while US total exports grew by 2.9 %. China’s exports to the US increased by 1.1 % in the same period, also a smaller increase than in total exports (up 3.0 %).

Even as the respective market shares for US-China goods trade has declined, the market shares of other trading partners (e.g. countries in Southeast Asia and Mexico) have grown. This likely indicates that supply chains have adjusted and a portion of trade transits through third countries to avoid tariffs. The shifting of trade flows through third countries can be taken into consideration by studying trade in value-added terms. Indeed, while direct US-China trade has declined in recent years, the share of Chinese value-added in US manufacturing remained unchanged between 2018 and 2023 (see BOFIT Policy Brief 10/2024). Although the United States has sought for years to lower its China exposure, reduction in its dependence on China is extremely difficult. Global production chains are an integral part of the global economy and China accounts for a huge share of global manufacturing.

Chinese goods exports to the United States far exceed US exports to China

Sources: IMF DOTS and BOFIT.