BOFIT Weekly Review 43/2024

Russia lays out hydrocarbon-based energy strategy

The Russian government prepares a national energy strategy at regular intervals. The 2009 strategy paper, which covered the period 2009–2030, was updated in 2020 and extended to 2035 (ES-2035). The energy strategies are usually rather general descriptions of future targets for the energy sector as a whole. The strategy papers, however, also include branch-specific targets for production and export volumes. Even if the final strategy paper is ultimately quite limited in its impact, it may shed light into how the government thinks about the future of Russia’s energy sector.

The current version of the strategy, which extends through 2050, has been in the works for over two years and should be ready by the end of this year. Drafting of earlier strategy papers has involved input from various ministries, research institutions and energy experts. This time around the drafting process has been largely limited to persons within the administration. The strategic outlines were supposed to be finalised by the end of September, when Moscow hosted the Russian Energy Week forum (September 26–28). The keynote speakers at the energy forum were Russian president Vladimir Putin and Equatorial Guinean president Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo. Both stressed the need for cooperation among “friendly” states to secure stable access to energy supplies. In his address, Putin praised the fact that Russian energy consumption last year reached its highest level since the breakup of the Soviet Union.

Based on Kremlin statements, the latest strategy is expected to be based on an assumption of increasing hydrocarbon use. The text is also likely to stress import substitution and domestic development of technical solutions, the growing importance of Asian markets, as well as the broader significance of Russia’s energy sector in foreign policy and national security. According to media reports, the draft version assumes production and exports of natural gas and coal will increase significantly by 2050. Oil exports are expected to remain roughly at their current levels for the entire strategic outlook period. This probably is based largely on assumptions of robust economic growth in Russia’s main export markets in Asia and impeded progress in electrification of transport systems.

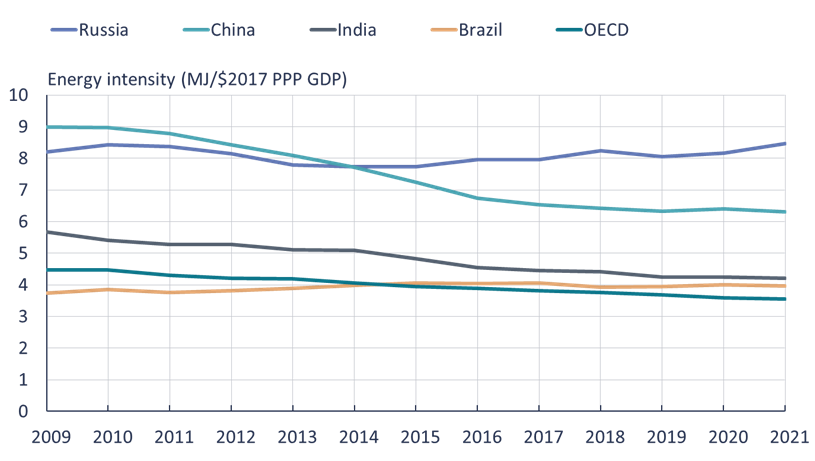

In this Russian worldview, low carbon energy generation is treated as a sideshow in development of future energy markets and greater energy efficiency is scarcely mentioned. Russia is a distinct outlier country as its use of primary energy in relation to GDP has been on the rise. In other words, the energy intensity of the Russian economy has not improved at all over the past decade.

Unlike many countries, Russia’s energy intensity ratio is about at the same high level as it was 15 years ago

Note: Energy intensity of primary energy is an indication of how much energy is used to produce one unit of economic output. A lower ratio indicates that less energy is used to produce one unit of output.

Source: World Development Indicators.

The latest International Energy Agency (IEA) World Energy Outlook sees global demand for hydrocarbon energy products starting to decline already next year. In addition, oil and coal demand in China, Russia’s biggest export market, is likely to decline sharply as the country electrifies and continues to build out its renewable energy infrastructure. The latest Central Bank of Russia analysis, which follows similar lines to those of the IEA, mentions the potential risks of China’s energy transition to the outlook for Russian exports of coal and oil.

Russia’s plans for expansion of coal and natural gas exports requires capturing of a significantly larger global market share and redirection of exports to relatively new markets in India and Southeast Asia. Increasing market share in a shrinking market may be challenging for Russia, which is one reason some analysts argue that the new energy strategy relies on overly optimistic assumptions.

The draft version of Russia’s energy strategy assumes increased hydrocarbon output in coming decades

Note: ES-2050 refers to media reporting on the targets mentioned in Russia’s latest energy strategy draft. IEA refers to energy consumption forecasts under the IEA’s 2024 World Energy Outlook “Stated Policies” scenario. The blue bar indicates the change from 2023 to 2030, and the teal bar shows the change from 2030 to 2050.

Sources: IEA WEO 2024, Vedomosti, BOFIT.

Lack of viable export routes

In coal and natural gas, Russia’s main future challenges are flagging global demand and logistical problems. Russia must find new ways to get its hydrocarbon commodities to global markets. Maintaining oil exports during the Ukraine war has required considerable investment in procurement of old oil tankers for Russia’s “shadow” commercial shipping fleet. The cost of shipping oil by sea is relatively cheap, so longer shipping distances and overpriced vessels still do not make oil-exporting unprofitable.

Coal markets on the other hand have been hit with the EU import ban, shifting logistical routes and capacity constraints on Russia’s railway system that have put producers, at least temporarily, in dire straits. Coal production this year has declined especially in Kemerovo, Russia’s main coal producing region. Kemerovo governor Oleg Tokarev reports that all coal bunkers and silos are full, even if the region’s production contracted in the first half of this year by 6 % y-o-y. In the first six months of this year, exports of coal from Kemerovo to Western markets declined by 21 % y-o-y, while exports to Asian markets increased by just 3 % due to transportation hitches. The price ceiling on coal is fairly low as its bulk and weight often make transportation costs the biggest factor in determining its cost-competitiveness. Growth in future production and exports requires that Russia make significant investments in its rail network, rolling stock and export harbours.

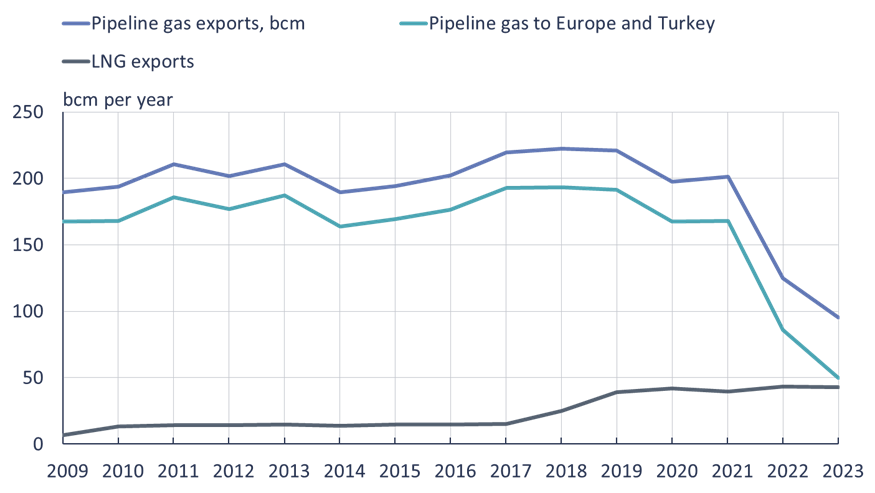

Global demand for natural gas is predicted to remain strong for decades, while the export outlook for Russian pipeline gas is fairly bleak. In 2021, Russia transmitted via pipeline about 201 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas, of which over 80 % went to Europe and Turkey. With the cessation of gas exports to EU countries, Russian pipeline gas exports fell to about 120 bcm. In 2023, pipeline gas exports amounted to slightly less than 50 bcm for Europe and Turkey, about 20 bcm for China and about 25 bcm for countries in the Eurasian Economic Union (mainly Belarus).

Planning of new pipeline routes takes time, and even so, the loss of the EU market cannot be fully compensated for by building new pipelines. For example, agreement on construction of the Power of Siberia pipeline running to China took place in 2014, but the first gas only reached the Chinese market in late 2019. This December, the Power of Siberia pipeline will finally reach full capacity (38 bcm a year). Russia and China agreed in late 2022 on construction of a new pipeline in Russia’s Far East. The proposed pipeline would have an annual capacity of 10 bcm a year with commissioning beginning at the start of 2027.

Russia has plenty of available gas production capacity, but increasing exports requires massive investment in liquefied natural gas (LNG) production, specialised ports and Arctic ice-sea-traversing LNG tankers. Russia currently operates two major LNG facilities, one on Sakhalin Island on the Sea of Okhotsk in the Far East and another in the Yamal peninsula on the Kara Sea in Northern Siberia. Western sanctions have delayed construction of new LNG facilities and forced planners to revise their profitability calculations. Even bringing gas exports back to pre-war levels will require more than doubling LNG exports from their current level, a situation unlikely to occur for a while.

War has decreased Russian gas exports (bcm per year)

Source: Energy Institute Statistical Review of World Energy, 2024.