BOFIT Weekly Review 09/2024

Russian population in decline

At the end of last year, Russia has 146.2 million people living permanently in the country. Excluding the population living in Crimea, illegally annexed in 2014, Russia’s 2023 population was about 144 million. Russia’s population peaked in 1993 at around 149 million.

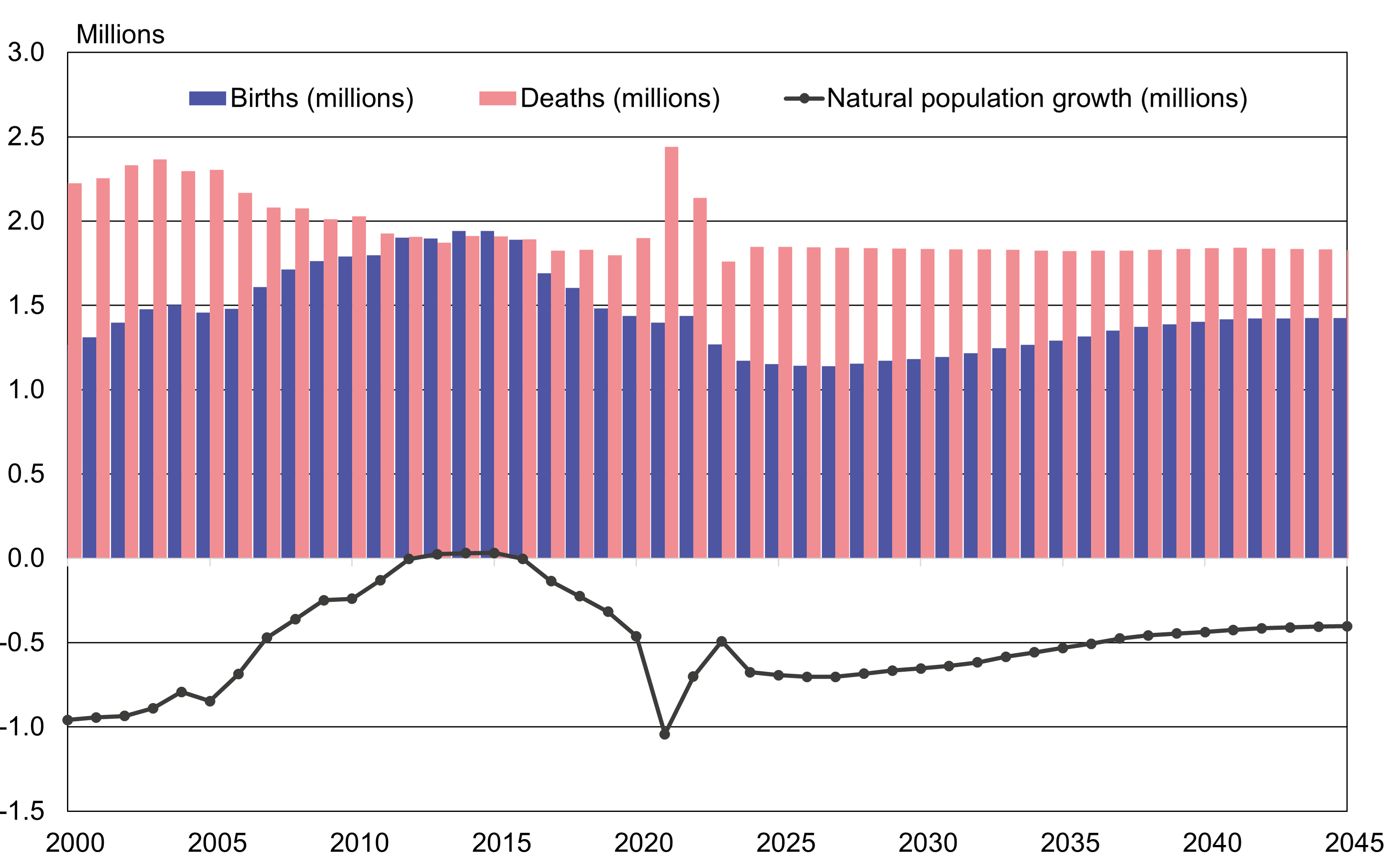

Russia’s natural population growth has be negative or flat since 2000, which means that overall deaths have outnumbered births. Only 1.27 million babies were born in Russia last year, the lowest number since 2000. The drop in the birth rate echoes the massive drop in the 1990s following the breakup of the Soviet Union. The cohort of young adults aged 25 to 30 is now about 5 million smaller than it was a decade ago. The number of births is expected to remain at the current low level at least until the end of this decade.

The mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 persons per year) has fallen throughout the past two decade, while the expected lifespan of Russians has increased (but not enough to make up for declining births). The number of deaths last year outstripped births by about 440,000. 2021 witnessed a significant rise in mortality from the Covid-19 pandemic. At that time, deaths outnumbered births by about 1 million. As in many countries, the Russian population is also greying. Rosstat’s latest population forecast expects the pension-age share of the population to rise from 24 % at present to around 27 % in the 2040s.

Deaths should outnumber births over the next two decades

Years 2024-2045; Rosstat forecast middle scenario.

Source: Rosstat/ CEIC.

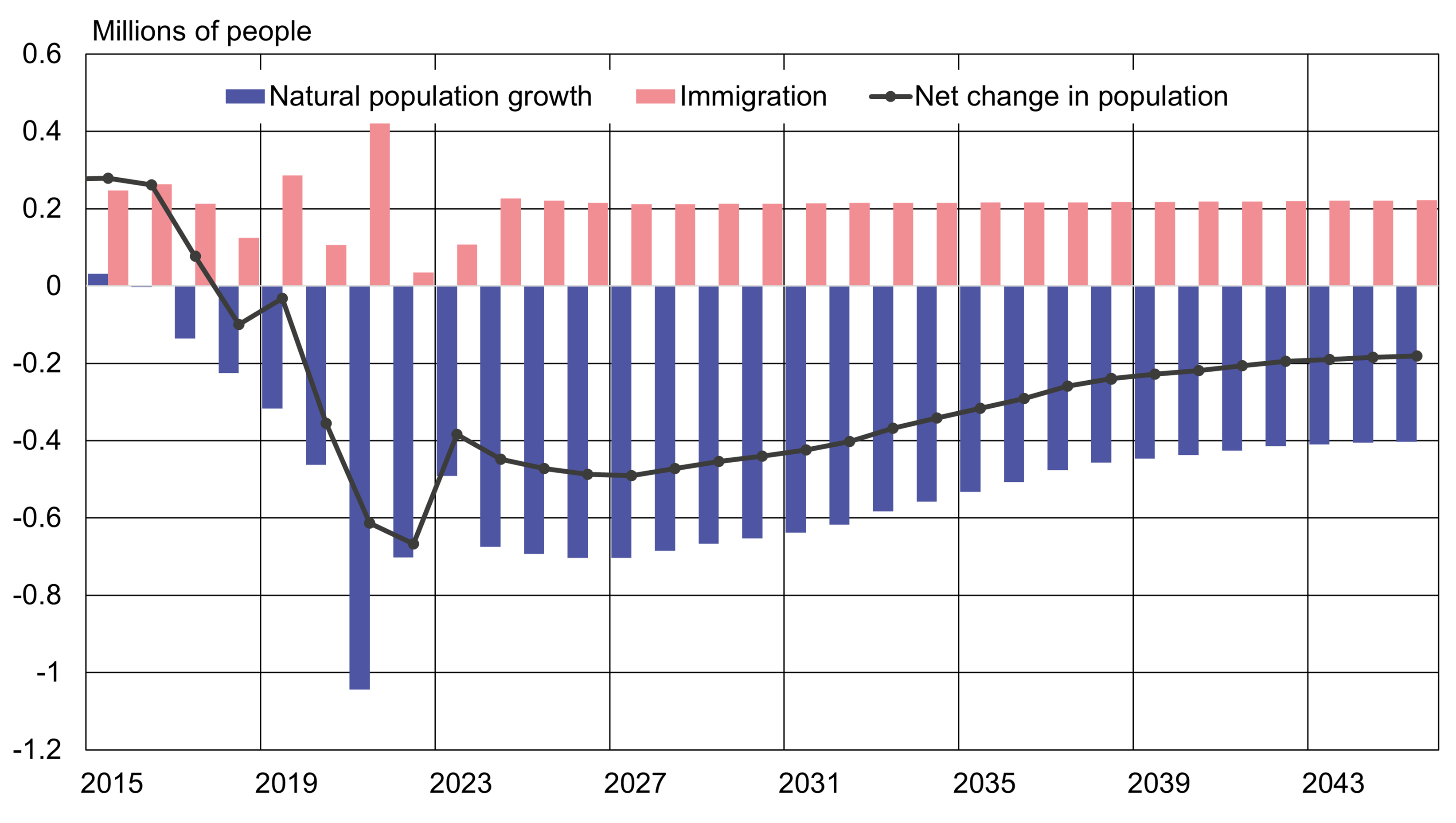

Immigration slows population contraction

Russia’s declining population trend has mainly been offset by a net influx of people from Central Asia. Official records show net immigration last year of over 200,000 people, or about half of the natural population decline. Indeed, without significant numbers of migrants and the increase in population from occupied territories, Russia’s population would have shrunk by about 12 million people since 2000 and about 5 million over the past ten years.

Russian immigration and emigration figures are imprecise. Russian citizens who leave the country rarely inform local officials of their new domicile abroad. Similarly, persons with expired residence permits are automatically assumed to have left the country, when in fact such persons may not always leave the country. By several estimates, roughly 900,000 people have also left the country due to the war in Ukraine and mobilisation of reserves. Nearly all of these persons may remain on the books in Russia. This practice is partly the reason the national population figure has gone through several adjustments since the 202o census. The impacts from the 2020 census were still seen, for example, in the 2022 population figure, which showed the population increasing.

In addition to permanent population, a large number of migrant workers live in Russia In January-September 2023, roughly 3.6 million people entered Russia for work, suggesting that last year the flow of migrant workers to Russia was back to pre-pandemic levels. About 45 % of the arrivals come from Uzbekistan, about 28 % from Tajikistan and 14 % from Kyrgyzstan. These figures only record border-crossings, and many seasonal migrant workers cross into and out of Russia several times a year. At the moment, clear data on the numbers of migrant workers are simply unavailable.

In order to offset its population decline, Russia needs to increase the annual numbers of immigrants and migrant workers. However, some observers note that the potential pool of new migrants has been reduced by fears of additional mobilisation rounds in Russia and improving economic conditions in the countries that have traditionally provided migrant labour to Russia. Under Rosstat’s “middle” demographic scenario, net migration to Russia would hardly change from its current level over the next two decades.

Even with immigration, Russia’s population should contract over the coming decades

Years 2024-2045; Rosstat forecast middle scenario.

Source: Rosstat/ CEIC.

Unemployment hits record lows

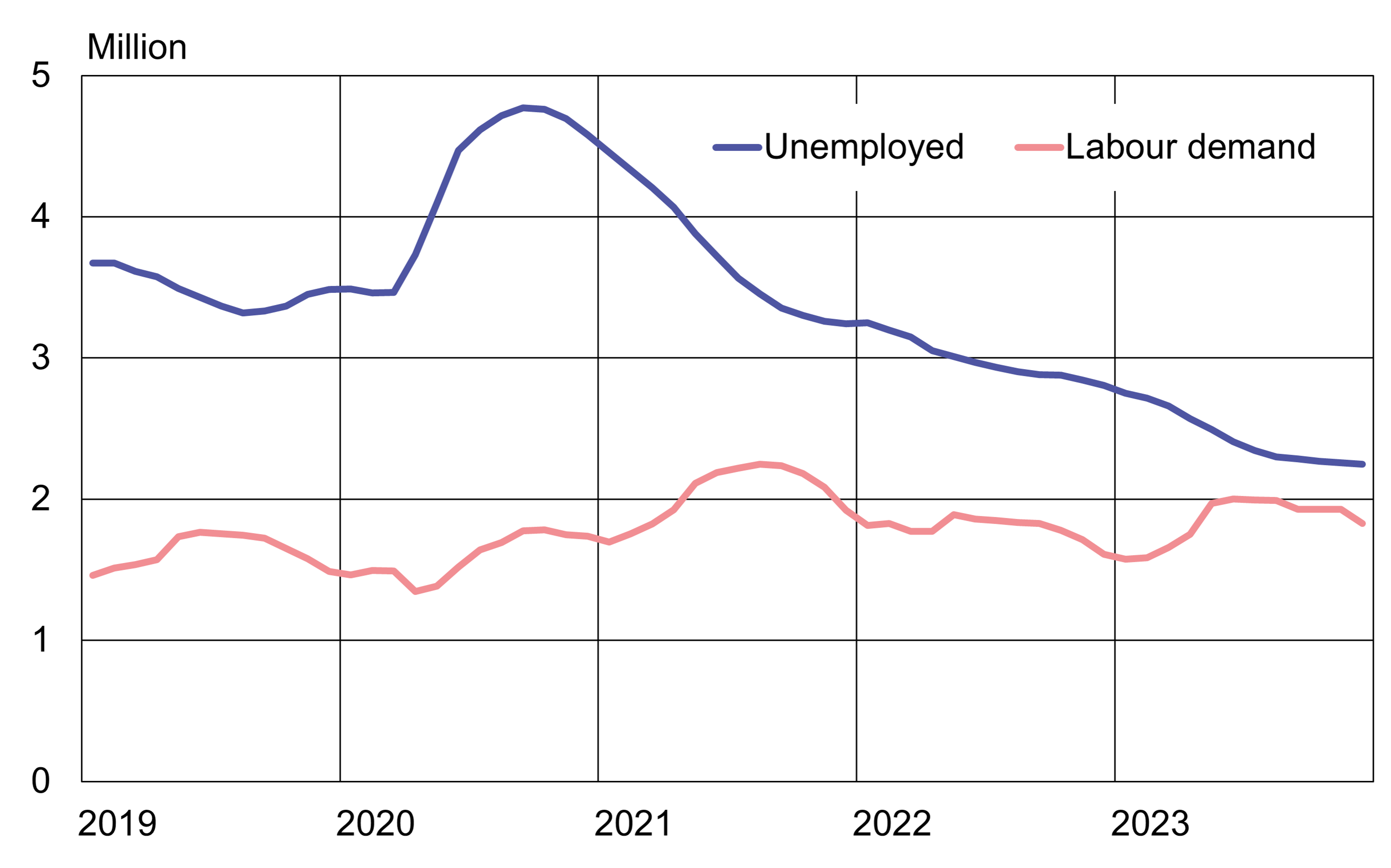

Russia’s demographic structure was altered substantially in the post-Soviet 1990s due to a sharp drop in births. With that small cohort now in the workforce and the shift to a wartime economy, significant labour shortages have emerged. Workers in Russia have traditionally preferred flexibility in wages and hours to layoffs or job uncertainty, which has kept labour participation rates fairly stable. In bad times, workers are willing accept lower pay, as well as forego bonuses and wage benefits. When times improve and labour demand rises, wages and other forms of compensation shoot up. The current tightness of labour markets is well reflected in the increased average wage (up 15 % in November 2023), while the unemployment rate has plunged to all-time low for the post-Soviet era (3 % in December 2023). Unemployment is lowest in industrialised regions in the half of the country closer to Europe. In regions more remote from Europe, particularly North Caucasus Federal District, as well as certain regions in the Siberia and the Far East Federal Districts, unemployment remains well above the national average. About 500,000 of Russia’s 2.2 million unemployed live in the North Caucasus Federal District. According to figures from Russia’s unemployment offices, the number of officially registered unemployed nationally was only about 400,000 last December.

The tightness of the Russian labour market is reflected in last year’s increase in labour force participation to 61.3 % (much higher than pre-pandemic levels). The share of part-time workers in the labour force also declined to record low levels in 2023. The drop in part-time work was down by 80 % y-o-y in branches involved in metal refining, metal fabrication and machine-building. Russia’s current economy is running flat-out; it has no extra labour buffer or additional worker pools to draw upon. As a result, the pace of output growth may have peaked. Soaring wage growth, especially in war-related manufacturing branches, has increased inflationary pressures.

The number of unemployed has declined in recent years, while demand for workers has remained strong

The number of unemployed persons based on ILO methodology (3-month average). Labour demand based on number of available positions posted at employment offices.

Sources: Rosstat, CEIC.