BOFIT Weekly Review 48/2022

Reducing emissions and slowing climate change also matters for Chinese economic performance

The COP 27 UN Climate Conference held last month in Egypt, adjourned with little progress towards climate goals. The biggest achievement was a general agreement on establishment of a loss and damage fund that could be used to compensate poor countries for harms caused by climate disruption. While China officially supports establishment of the fund, it said that funding should come from developed economies responsible for most of the planet’s historical anthropic carbon legacy. China’s role in the fund is unclear. It has not committed to providing funding or the notion that reparations should go only to the poorest countries. During the COP 27 meeting, China and the US representatives met separately and agreed to resume their bilateral formal climate dialogue that had been on ice since August.

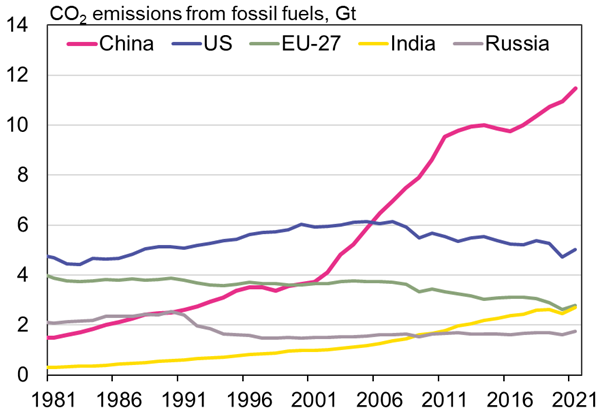

China is the world’s largest polluter, generating 27 % of global carbon dioxide emissions and a third of greenhouse gas emissions. In 2020, China announced that its CO2 emissions would peak by 2030 and thereafter decline so that carbon neutrality would be achieved by 2060. China’s goals, however, are insufficient to keep global warming at the 1.5°C target agreed under the 2015 the Paris climate agreement. To reach the Paris target, China needs to achieve carbon neutrality at least a decade earlier. China has, however, continued to increase its coal-fired power generation and domestic coal production referring to energy security and self-sufficiency. Even if new coal plants pollute less than old ones, they still need to be phased out as quickly as possible. China’s CO2 emissions continued to rise last year, increasing by 5 %.

The World Bank released its China Country Climate and Development Report in October. The report, which deals with the costs of climate disruption and policy recommendation on emissions reduction, notes that the climate risks facing China are enormous and cloud the country’s long-term growth prospects. A large part of the population and economic infrastructure is located in areas susceptible to climate risks. For example, a third of Chinese GDP is generated in coastal areas sensitive to the effects of storms, flooding and coastal erosion. In the interior of the country, the biggest threats are heat, drought, and water insecurity, all of which hit agriculture particularly hard. The direct losses from natural hazards are already materialising and have averaged around 0.5 % of GDP per year. The risk scenarios in the report suggest those costs could exceed 2 % of GDP by 2030. The costs hit poor households hardest.

Unlike advanced economies, the report notes that China is poised to separate economic growth from emissions growth much faster and at a lower income level. The precondition for success, however, is implementation of broad structural economic reforms. The transition would make a large chunk of China’s carbon-intensive capital stock useless, displace workers in polluting sectors and raise energy prices at least in the short-term, with the benefits accruing later. For China to reach its 2060 carbon neutrality goals would require first defining shorter-term targets and starting from phasing out the use of coal in energy production. According to the report, the power and transport sector alone requires 14 trillion dollars (about 1 % of annual GDP) in increased investment by 2060. The cost rises to 17 trillion dollars in the scenario with accelerated emission reduction and achieving the emission peak before 2030. Nevertheless, investment would necessarily be frontloaded. The economy could adjust faster and avoid some of the foreseeable costs if decarbonisation policies are combined with structural reforms that rebalance the allocation of capital and labour, and reduce the barriers to market entry and exit for firms. The report stresses that the economic impacts of decarbonisation are likely to be manageable in China and could even promote growth by improving air quality, enhancing health and increasing productivity.

China’s CO2 emissions continue to rise. Achieving carbon neutrality by 2060 would require massive measures.

Sources: Our World in Data CO2 Greenhouse Gas Emissions dataset and BOFIT.